In 1959, at the age of 26, George Schaller traveled to central Africa's Virunga volcanoes to study the mountain gorilla. As the first biologist to live among them, Schaller dashed the myth of the gorilla as brute. "No one who looks into a gorilla's eyes can remain unchanged," he wrote. "The gap between ape and human vanishes; we know that the gorilla still lives within us."

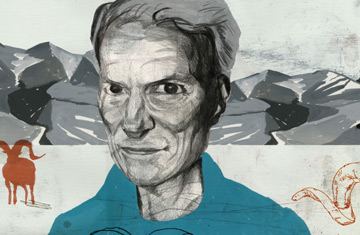

That soulful connection between human and animal would be the thread connecting all of Schaller's later work: his travels among the lions of the Serengeti, the jaguars of Brazil, the giant pandas of China's Wolong Mountains. In time Schaller became known as the world's finest field biologist, the lean and hard-eyed figure of Peter Matthiessen's classic 1978 book The Snow Leopard. He seemed almost out of place in the 20th century, better suited to the great Victorian age of exploration.

But Schaller is not merely an adventurer. Learning about the great animals of the natural world drove him to protect them. He realized that the kinship he divined between man and the big apes and cats — the charismatic megafauna — could make others more willing to protect nature as a whole. He understood that the big animals could serve as spokesmodels for the natural world. As vice president of science and exploration for the Wildlife Conservation Society, Schaller helped to establish over 20 nature reserves and parks — from the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to the 115,000-sq.-mi. (300,000 sq km) Chang Tang Nature Reserve in Tibet.

Now 74, Schaller is trying to create an international refuge across parts of Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan and China, designed to shelter the majestic and endangered Marco Polo sheep. In pursuit of this dream, he has crisscrossed these harsh lands, where violence against both animals and humans is a way of life. If Schaller pulls off this peace park, he may help to preserve another megafauna in need of occasional protection: man.